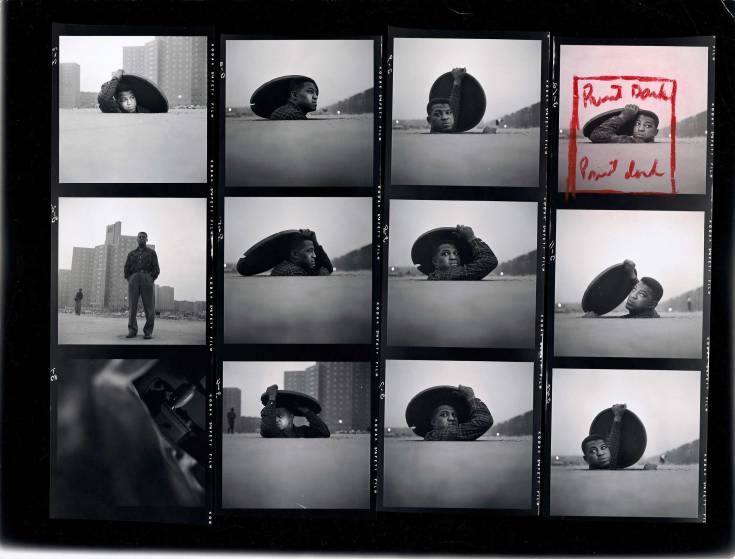

Gordon Parks, the renowned LIFE magazine photographer, and Ralph Ellison, the acclaimed novelist, shared a vision of Harlem — and that vision was grim. During the decade after the end of World War II, they collaborated twice on projects that were intended to reveal underlying truths about the New York City neighborhood that was sometimes called the capital city of black America. Their first effort, in 1947, was never published. In the second, “A Man Becomes Invisible,” which appeared in LIFE on Aug. 25, 1952, Parks interpreted Ellison’s recently published novel,Invisible Man, through images that were by turns surreal and nightmarish.

Parks and Ellison were friends as well as collaborators, and both were strangers to Harlem. Their roots, in Kansas and Oklahoma respectively, were culturally and geographically far removed from what Parks once called Harlem’s “shadowy ghetto.” While other African American artists celebrated Harlemites’ cultural achievements, Parks and Ellison both mourned the psychological damage that racism had inflicted on them. There was no room in their Harlem for a Duke Ellington or a Langston Hughes, or even for the ordinary pleasures of love and laughter. Instead Harlem was, in Ellison’s words, “the scene and symbol of the Negro’s perpetual alienation in the land of his birth.”

It is likely that the idea for the visual homage to Invisible Man came from Parks. The book was, after all, the work of a close friend—and had been partly written while Ellison was housesitting for the Parks family in 1950. LIFE’s editors would have been receptive to the idea. Invisible Man had been published to nearly universal critical acclaim and was one of the most talked about books of the year.

“A Man Becomes Invisible” was not LIFE’s first visualization of a book by an African American writer. For “Black Boy: A Negro Writes a Bitter Autobiography,” published in 1945, photographer George Karger recreated scenes from Richard Wright’s highly praised memoir. The images were dramatic but straightforward, illustrating the book rather than interpreting it. Parks, on the other hand, produced a self-consciously subjective interpretation.