"Our helicopter was heading over the Niger Delta, across a vast and unstable sky, with gray clouds surging above. I was sitting behind the pilot, and behind me, gazing out a starboard window, was Edward Burtynsky, a Canadian photographer known for his sweeping images of industrial projects and their effects on the environment. For three decades, he has been documenting colossal mines, quarries, dams, roadways, factories, and trash piles—telling a story, frame by frame, of a planet reshaped by human ambition. For one seminal project, sixteen years ago, he travelled to Bangladesh to shoot decommissioned oil tankers that were being ripped apart by barefoot men with cutting torches. Those images of monumental debris—angular masses that appear to emerge from sediment like alien geology—remain transfixing. Carefully choreographed, shot in hazy and ethereal light, they echo the sublime power of a Turner landscape even as they portray a reckoning with garbage.

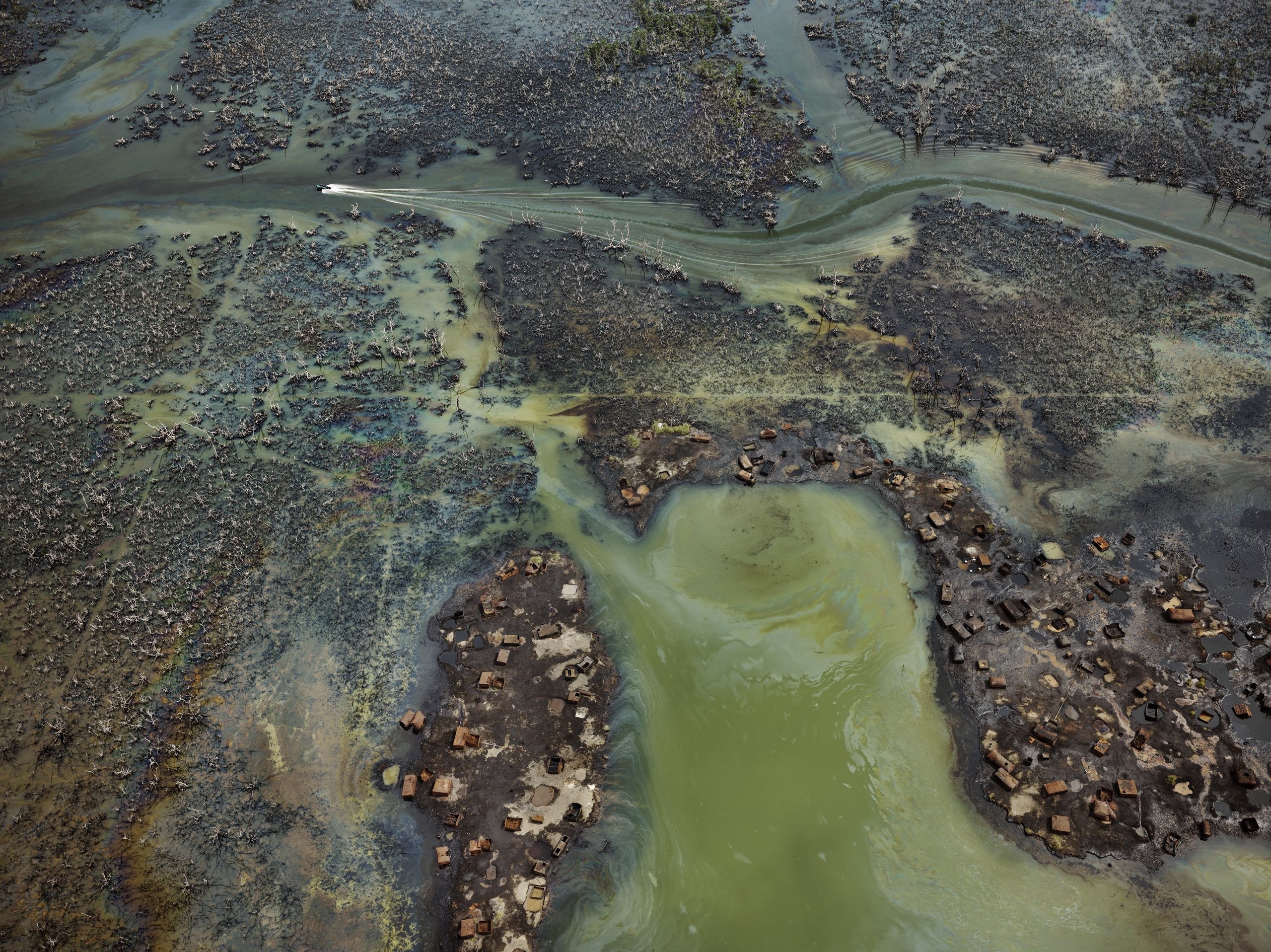

Burtynsky had hired our helicopter for four hours, at a rate of two dollars per second, to document the ravages of oil theft in the estuaries along Nigeria’s southern coast. Since crude was discovered in Nigeria, in 1956, it has brought wealth and corruption, impoverishment and armed conflict—a global symbol of squandered possibility. “Wherever there is oil, especially in developing countries, by and large there is a lot of pilfering, and society doesn’t really enjoy the profits,” Burtynsky had told me. “In the Niger Delta, the pushback from the have-nots has been to go in there and start pirating the oil.” In recent years, parts of the delta have taken on the atmosphere of a war zone: hidden among mangroves and low bush, villagers and local militias have established countless makeshift distilleries to refine crude stolen from pipelines, while dumping tons of oleaginous waste back into the ground. The government has estimated that two hundred and fifty thousand barrels are stolen daily, but nobody really knows. Last year, Nigeria’s newly elected President, Muhammadu Buhari, vowed to end the theft, noting, “The amount involved is mind-boggling.”

In the heat of the helicopter’s cabin, Burtynsky adjusted a pair of orange-tinted sunglasses on his nose. He was wearing jeans, a T-shirt, and a loose button-down, to shield his arms from the sun. His large frame was compressed into his seat, and—because he would be shooting out an open door—he was buckled to a military-grade safety harness. As sweat dampened his graying hair and goatee, he had begun to take on the faded crispness of an engineer logging too many hours in the field.

At the age of sixty-one, Burtynsky conducts his shoots with unceasing energy—waking at dawn, working past midnight—and rarely succumbs to irritability, an easygoingness polished by years of creative adversity in difficult places. He had gone up in the helicopter two days earlier, but the conditions—bright sunlight that he classified as “snarky”—had been less than ideal. He spent the following day at a military airstrip in Port Harcourt, the regional capital, debating whether to go up again. He prefers to photograph in bright overcast, when shadows fade away. As he told me, “When the light is soft, you sense the volume of a place.” Rain would ruin the shoot, but so would clear skies, and the weather was mercurial. Few photographers can spend two dollars per second for a flight, and even for Burtynsky—whose prints sell for tens of thousands of dollars, and who can raise millions for his projects—the cost is significant. “I wonder if we should risk it,” he had murmured. He munched on homemade granola. He napped on metal chairs. He decided not to risk it.

The next morning, though, a cloud canopy seemed like it might hold, and so he told his producer, Jim Panou, to ready the aircraft. Panou has been working with Burtynsky for more than a decade, solving logistical problems with a hardheaded intensity that is belied by his soft, rounded features. A photographer in his own right, he devotes much of his time to working on Burtynsky’s international shoots. Using Google Earth, Panou had scanned hundreds of square miles of the delta in search of the most dramatic of the illicit distilleries. Everywhere we went, he carried two iPads, and even as we waited in the military airport he was still searching for hidden sites: “Ooh, that’s a pretty hellish one.” Burtynsky told me, “He’s like an extension of my consciousness.”

As the two men prepared in the chopper on the tarmac, very little needed to be said. With Panou’s help, Burtynsky readied his gear, and then he fell into contemplation. “Some birds over the runway,” the pilot announced, and he joked about how much extra it would cost if he lifted off and had to avoid them: “Put a big old barrel back there and put hundred-dollar bills in.” Burtynsky did not respond; he sat silently as we waited for the flock to pass. “O.K.,” the pilot said. “Ready for takeoff.”